The Last March Of Martin Luther King Jr.

By Drew Dellinger.

In the months leading up to his assassination in 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made some of his most searing pronouncements against white supremacy, the Vietnam War, and U.S. imperialism. But more than at any other time in his life, King’s final focus was on poverty and economic injustice.

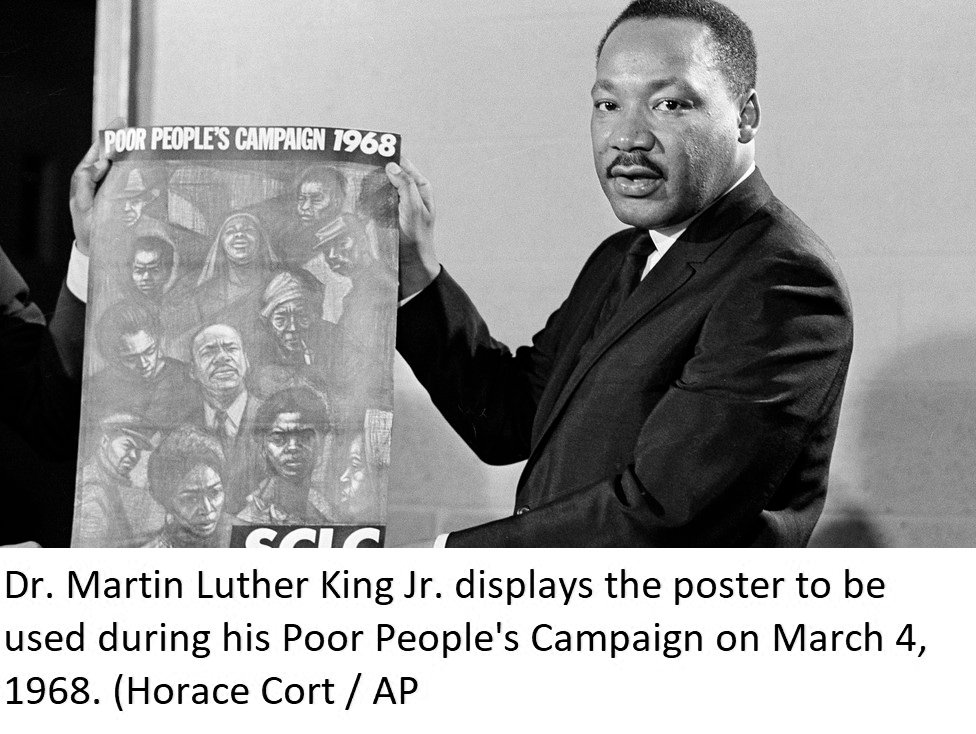

By the winter of 1968, Dr. King and his organization were embarking on one of their boldest projects yet, a Poor People’s Campaign that would bring a multiracial coalition to the nation’s capital to demand federal funding for full employment, a guaranteed annual income, anti-poverty programs, and housing for the poor. Announcing their new initiative, King said, “The Southern Christian Leadership Conference [SCLC] will lead waves of the nation’s poor and disinherited to Washington, D.C., next spring to demand redress of their grievances by the United States government and to secure at least jobs or income for all.”

The idea for the Poor People’s Campaign had been sparked by Senator Robert Kennedy, in a simple message passed by Marian Wright (later Marian Wright Edelman) to King months earlier. At the close of a conversation between Kennedy and Wright, the senator had said, “Tell Dr. King to bring the people to Washington.”

If Kennedy’s comment provided a final catalyst, the seeds of the Poor People’s Campaign can be found a year earlier in the Mississippi Delta. In June 1966 King and his closest associate, Reverend Ralph Abernathy, were visiting a Head Start daycare in Marks, Mississippi, a tiny town in Quitman County—the poorest county in the country. It took them a moment to notice that the bright-eyed children were malnourished. At lunchtime, the teacher brought out a brown paper bag of apples and a box of crackers.

When she cut an apple into quarters, and gave one slice, and four or five crackers, to each of the waiting, hungry students, King and Abernathy exchanged solemn glances. This was all the children had for lunch, they realized with shock. Neither man had ever seen poverty like this. Dr. King began weeping, and had to leave the classroom. That night, lying on a motel bed and staring at the ceiling, King said, “Ralph, I can’t get those children out of my mind.”

For the next year, King weathered setbacks in Chicago, challenges to his leadership from the emerging advocates of the Black Power movement, questions about the relevance of nonviolence in the face of increasing urban rebellions, and a storm of controversy over his stand against the war in Vietnam. But the issue of poverty never left his mind.

At the SCLC staff retreat in November, King revealed his plans for a poor people’s march to Washington to his colleagues and called for a new “stage of massive, active, nonviolent resistance to the evils of modern corporate society.” Sixteen months after he had been moved to tears in Marks, King was on the cusp of bringing 3,000 poor people—“a nonviolent army,” a “freedom church of the poor,” he called it—to Washington, D.C., to demand a “radical redistribution of economic power.”

King had long lived under a shadow of danger. His colleague Walter Fauntroy remembered that when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, King gazed out a window and said, “Walter, you know, if they’ll kill a president, I won’t live to be 40.” As author David Garrow states, “In the last 12 months of his life, King represented a far greater political threat to the reigning American government than he ever had before.” As King began to question “why are there 40 million poor people in America” he knew he was “tampering and getting on dangerous ground … because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong with the economic system of our nation.” But he did not back away from economic injustice.

On March 4, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent an internal memo stressing the urgency of the counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) the FBI had initiated in August 1967 against what they called “Black-Nationalist Hate Groups.” The March 4 memo expanded the COINTELPRO from 22 to 44 FBI offices, and, for the first time, specifically named Dr. King. In the memo, Hoover ordered his agents to “prevent the RISE OF A ‘MESSIAH’ who could unify, and electrify, the militant black nationalist movement,” adding that “King could be a very real contender for this position,” should he abandon nonviolence. Like King, Hoover recognized the potential power of a unified movement for justice.

On Thursday, March 14, 78 “non-black” leaders traveled to Atlanta from 17 states for a planning meeting of the Poor People’s Campaign Steering Committee. They came from Native American, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and white communities, representing 53 organizations. “It has been one of my dreams that we would come together,” King told the gathering. Their “declaration of unanimous support” for the Poor People’s Campaign, writes Stewart Burns, was “a breakthrough of major proportions, the high point of the entire campaign.”

As King traversed the Mississippi Delta barnstorming through rallies in Greenwood, Clarksdale, and Grenada to recruit for the Poor People’s Campaign, he never lost sight of the connection between race and poverty. Speaking in Laurel, Mississippi, King placed white supremacy at the nexus of the country’s crisis, stating, “The thing wrong with America is white racism.” A few days later he said, “However difficult it is to hear, however shocking it is to hear, we’ve got to face the fact that America is a racist country.”

Ten days before his assassination, King told an audience, “I think it is absolutely necessary now to deal massively and militantly with the economic problem … This is why in SCLC we came up with the idea of going to Washington, the seat of government, to dramatize the gulf between promise and fulfillment, to call attention to the gap between the dream and the realities, to make the invisible visible.”

But King would never make it to Washington. On February 1, two sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, Robert Walker and Echol Cole, were crushed to death in a horrible accident caused by a malfunctioning truck. After years of complaints about faulty equipment, low pay, racism, and other mistreatment, the deaths of Walker and Cole brought the sanitation workers in Memphis to the brink. On February 12, 1,300 workers walked off the job. The Memphis movement would soon become the first march of the Poor People’s Campaign. It would also be King’s last march.

Some on King’s staff were stunned that he would consider going to Memphis when they were so far behind in organizing the Poor People’s Campaign. But for King, the sanitation workers’ strike was the poverty campaign in microcosm. On March 18, he addressed the striking sanitation workers, and an energized, supportive Memphis community. “You are highlighting the economic issue,” King told a packed crowd of 15,000 at Mason Temple. “You are going beyond purely civil rights to questions of human rights.” At the end of the speech, King huddled with his staff, then came back to the microphone and announced he would return soon to lead a march with the workers through downtown Memphis.

Ten days later King was rushed from the scene when the Memphis march unraveled into window-breaking and looting. A Black teen was shot and killed by Memphis police. Profoundly dispirited, King confided to Stanley Levison—on a call monitored by the FBI—that the Poor People’s Campaign was in “serious trouble.” It was the first time a King-led march had turned violent. To show that nonviolent protest could still bring about radical social change, King concluded that his only choice was to return again to Memphis and lead a peaceful march—a march he would not live to lead.

In late May, the Poor People’s Campaign began to arrive in Washington. It would eventually include a mule train of 15 covered wagons that had departed from Marks, Mississippi. On Mother’s Day, Coretta Scott King and the women of the National Welfare Rights Organization led a march of 7,000 through Washington’s streets. A village of wooden structures—Resurrection City—was built on the National Mall near the Lincoln Memorial. Although Resurrection City was hampered by mud, muggings, and organizational difficulties, thousands did take part in weeks of demonstrations at federal agencies, and on June 19, more than 50,000 marched for economic justice in the last nonviolent mass mobilization of the 1960s.

But all of that was still weeks away on April 3 when Dr. King and Rev. Abernathy checked into room 306 of the Lorraine Motel.